The New

World

A Land of hope and opportunity

Starting out. Embarking on a new venture. Going for it.

Staying the course, come hell or high water.

Being an entrepreneur has always involved taking risks.

Dealing with knowns and unknowns.

Recognizing the dangers, but knowing you have to seize the day.

Arrival of Cartier in Stadacona in 1535. Louis-Félix Amiel, 1850.

In 17th-century France, life for most people was an endless cycle of epidemics and wars. But not everyone accepted this dismal fate. A few rebellious souls had a burning desire to start afresh . . . in the New World.

The perils of the voyage were as great as the prize: sailors and passengers were constantly on the lookout for bloodthirsty pirates and hungry sharks. And half of the ships sank before they even made it to New France.

Starting a new venture is not without risk. Today, only half of all startups make it past the five-year mark. We can learn valuable lessons from the entrepreneurs of the past: reading about their successes and failures can help us chart our way forward.

A Threemaster with the Amsterdam Coat-of-Arms, with Other Vessels, in a Storm. Ludolf Bakhuizen, 1700.

Champlain's Arrival at Quebec City. Henri Beau, 1903.

A VISIONARY

Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye

AMERICA'S FIRST MILLIONAIRE

Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye was an ambitious man willing to risk it all. In America he found fertile ground for his grand, and often excessive, schemes.

From the moment he settled in New France in 1659, Charles Aubert played a key role in the economic life of the colony. He ran a fur trade company and acquired 21 seigneuries, along with a large fleet of ships to transport goods from New France and the West Indies to Europe.

Although he was America’s first millionaire, he ended his life in poverty.

Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye was born on February 12, 1632, in the city of Amiens, in Picardy. He always described his parents as “worthy and poor,” even though they were part of the bourgeoisie. They made sure he got an education, which was rare at the time.

General View of the City of Amiens. Jean-Baptiste Lallemand, End of the 18th Century.

Charles Aubert studied geography, economics, business and navigation. As a young man, he was already on the lookout for business opportunities.

Boy Reading by Candlelight. Matthias Tom, ca. 1630-1655.

FROM ENGAGÉ TO SEIGNEUR

In 1655, at just 23, Charles Aubert boarded the Patriarche Abraham to cross the Atlantic. A group of Rouen merchants affiliated with the Company of One Hundred Associates had appointed him to look into the activities of Governor Jean de Lauson, suspected of corruption. The governor had little respect for the settlers and had gained a monopoly over the fur trade, to the detriment of the colony’s merchants and inhabitants.

Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye was now the Rouen merchants’ official agent and was granted the best available land in Quebec City and Beaupré, and on Île d’Orléans.

The businessman soon became the largest property owner in the colony, acquiring 21 seigneuries.

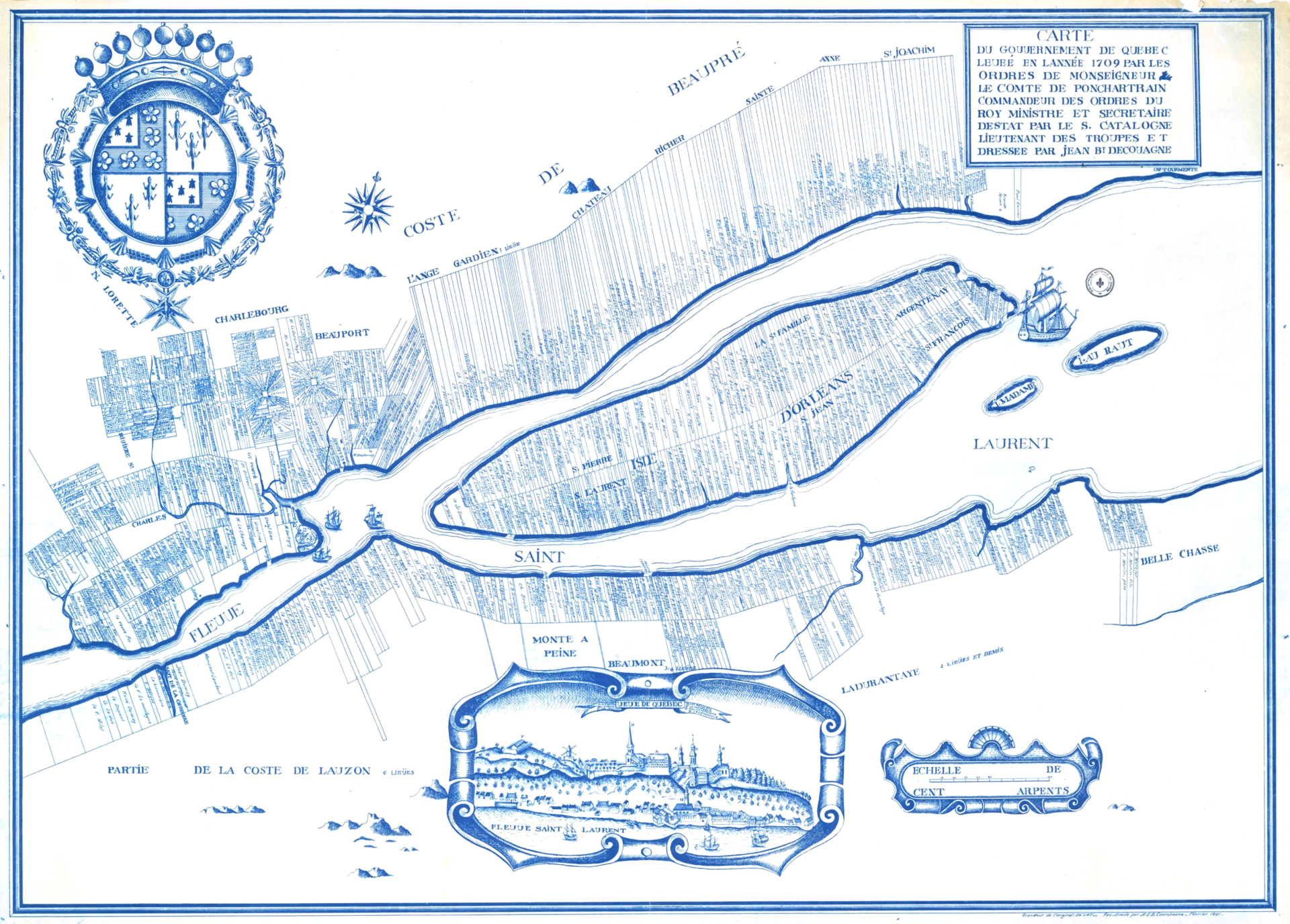

Map of Quebec City. Gédéon de Catalogne et al., 1921.

His empire extended from Montreal to Baie des Chaleurs.

Quebec as Seen from the East. Jean-Baptiste Franquelin, 1688.

In 1663, Jean Bourdon drew a map showing Quebec City and its few houses, warehouses and stores. Charles Aubert would become one of the city’s leading businessmen.

Authentic Map of Quebec City Made in 1663. Jean Bourdon, 1663.

FUR TRADER

At 31, Charles Aubert was a leading figure in the fur trade. In 1663, after 13 days of fierce competition, he successfully bid a fortune of 46,600 livres at an auction, gaining a monopoly over the Tadoussac fur trade for three years. His was the only company authorized to send furs to France.

Modifications of the Beaver Hat. Horace T. Martin, 1892.

THE COLONY'S GRAND FINANCIER

Charles Aubert was now considered the colony’s grand financier. He funded public spending and made loans to the community, becoming a widely respected figure.

His studies in administration served him well: he was a firm negotiator who knew the value of currencies around the world. The reports he sent to the Company of One Hundred Associates were concise and clear, and his elegant cursive handwriting was easy to read.

Playing card money, 50 livres – reproduction. 1714.

THE WIND TURNS

In 1670, beaver hats were no longer in style. The demand for fur declined and prices dropped precipitously. The economy of New France and Charles Aubert’s fortune were both in peril.

Refusing to give up, the stubborn businessman became a shipowner in the hopes of revitalizing the fur trade.

Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye teamed up with renowned explorer and fur trader Pierre-Esprit Radisson, hoping to revive the James Bay market. To no avail: the business continued to go downhill.

In 1678 alone, he lost a third of his assets.

QUEBEC CITY IN FLAMES

In August 1682, a terrible fire destroyed Quebec City’s Lower Town. Charles Aubert’s houses were spared, thanks to their slate roofs. He used his remaining cash to fund the rebuilding of the city and help his fellow citizens.

The Fire in the Saint-Jean Quarter, Seen Looking Westward. Joseph Légaré, ca. 1845-1848.

PHIPS’ ATTACK

On top of this disaster, there was the threat of an attack by the Bostonians. Charles Aubert had to sell guns to poor farmers who paid him in wheat, peas, flour and salt pork.

Quebec, City of North America in New France. Nicolas De Fer & Robert de Villeneuve, 1696.

Defence of Quebec, by Mr. de Frontenac. Rouargue frères, 1846.

By mid-October 1690, the Bostonians were approaching Quebec City. Charles Aubert, by then 58 years old, risked his life by leading the French ships to safety in the Saguenay. Admiral William Phips opened cannon fire on Quebec City from October 18 to 21, 1690. Thanks to the arms supplied by Charles Aubert, the Canadiens were able to defend themselves and defeat Phips’ troops.

Quebec City was saved.

THE SAVIOUR OF NEW FRANCE

On March 24, 1693, King Louis XIV granted Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye a patent of nobility for his acts of bravery and contribution to the rise of New France.

The Manor House in St. Roch Suburb. James Pattison Cocburn, 1829.

America’s first millionaire died poor and crippled with debt on December 20, 1702, at the age of 70.

Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye was buried in the paupers’ cemetery of the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Quebec City. He left behind a 41-year-old widow who had to support eight children in extremely precarious conditions.

Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye always remained true to his family motto: Vade ultra. Go beyond. Push your limits.